Kirsten Stolle’s art provides a useful lesson in the difference between looking and seeing. Her 2016 series Chemical Bouquet, for example, is, at first glance, a carefully rendered, collaged homage to the genteel floral still lifes of the Victorian era. But a more careful examination reveals something quite different. Sprouting among the leaves and petals are syringes, pill bottles, bloated cow udders, and barrels of Agent Orange, all elements of Stolle’s activist art that appropriates traditional forms as messengers of the dangers lurking in plain view, much of its critical gaze directed at global chemical and drug manufacturers such as Monsanto and Bayer. “For me, it’s most important to develop work that engages the viewer visually and conceptually without being overly didactic,” Stolle says. “The themes I examine are contemporary concerns, and I think most people will find some connection after primarily being drawn in by the aesthetics.”

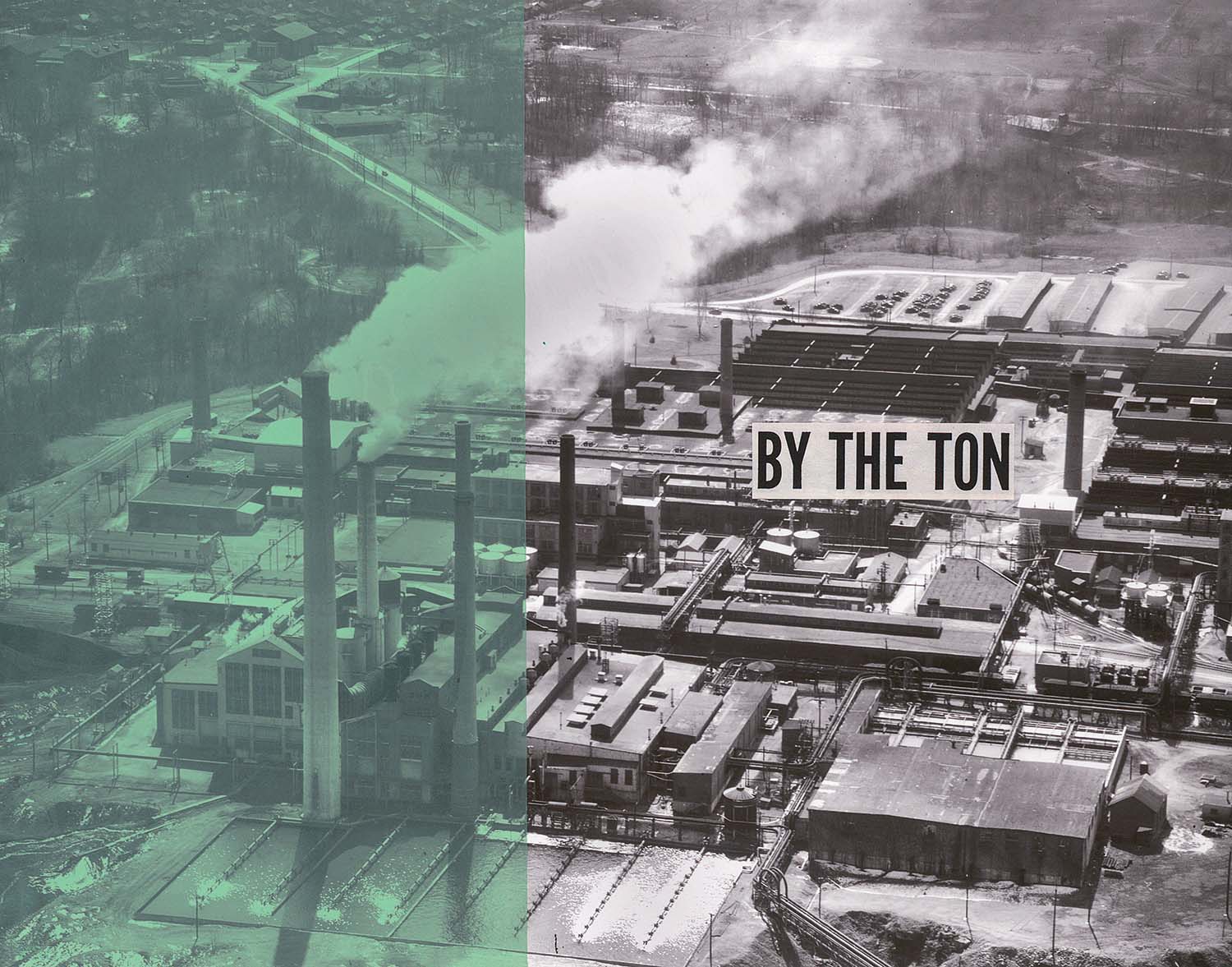

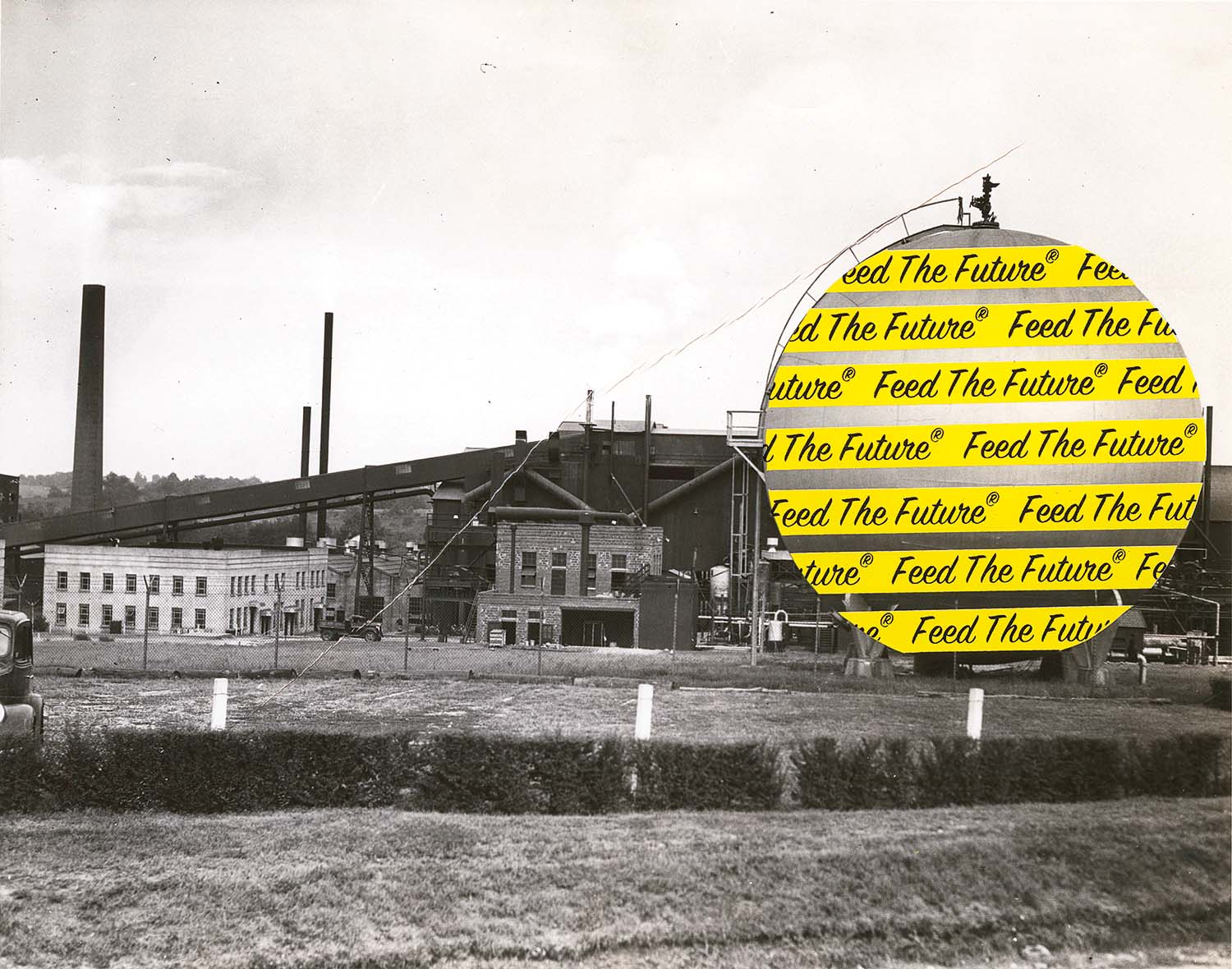

Stolle, who settled in Asheville six years ago after nearly two decades in the San Francisco art community, creates mixed-media work incorporating text from corporate advertising which she silkscreens over archival photographs, a visual commentary on the dangers of chemical warfare, genetically modified agriculture, nuclear arsenals, and other threats to global wellbeing. Disarm uses archival photographs of Cold War-era Nike missile installations, but drains them of their menace with colorful pen-and-ink tattoos. More somber is her By the Ton series, using text and photographs extracted from corporate advertising material,that examines the influence of the chemical industry on global food supplies. Stolle’s body of work finds company with such conceptual artists as Jenny Holzer, whose text-based pieces combine unrelated words and phrases to suggest new meanings, and the photography and collage work of Barbara Kruger and its commentaries on class and power. Even Rachel Carson’s strictly textual but seminal work Silent Spring finds a place in Stolle’s artistic landscape. But the presence of language in so much of Stolle’s work is deeply rooted in her own background.

“My mother is terrific with words and language, and often delves into writing projects,” she says. It was her example of activism that first brought toxic corporate histories to the fore for Stolle. In Santa Cruz in the early ’90s, her mom was involved in an anti-GMO protest against Monsanto using puppet theater, and her daughter was riveted.

“They were talking about inserting fish genes into strawberries to protect strawberries against cold temperatures,” she recalls. “Luckily that didn’t happen.” (Monsanto abandoned the idea after laboratory tests failed.)

Stolle’s earliest pieces in San Francisco were closer to pure abstraction, a collection of mixed-media work derived from natural and human forms incorporating wax, oil, graphite, and ink, among other materials. But the Monsanto alarm led to work more closely allied with science, heralded by 2010’s Anatomy of a Future Forest, a series that speculated on the effects of global warming on future plant and animal life. It was received with considerable acclaim. “The success of AFF gave me the confidence to pursue this new direction and visually explore GMO and agribusiness issues,” she says. The decision eventually netted her exhibitions in Berlin, Los Angeles, New York, and throughout the Southeast.

But while Anatomy brought attention to her work, the economic realities of coping with the Bay Area’s high cost of living began to catch up, and Asheville seemed to keep cropping up in discussions with friends about more affordable living. Stolle was fortunate to first visit the city in October 2010, when MoogFest, an event honoring late electronic-music guru Robert Moog, a long-time Asheville resident, was in full swing. “I loved the energy, the openness, the mountains and weather of Western North Carolina,” Stolle says. Three months later, she made the move.

Her reception has been congenial, most recently manifesting in a solo show slated for December at Tracey Morgan Gallery on Coxe Avenue. It will include not only previous work (Chemical Bouquet and By the Ton), but a new mixed-media project, Faith, Hope and $5,000, that Stolle calls “visual poetry” — a 16-piece gridded installation of cut and collaged book pages extracted from a mid-1970s corporate history of Monsanto.

“I’m broadening my work to include projects dealing with surveillance and corporate propaganda,” says the artist, “but I’m still committed to exploring the agribusiness and biotech influence on our food.” Naturally, her projects lean toward a certain critique. However, she notes that “giving the viewer space for an ambiguous reading or even an opposing view has created stimulating conversations.”

Kirsten Stolle’s solo exhibit “What Goes On Here” will run Friday, December 1 (opening reception 6-8pm) through Saturday, January 27, 2018, at Tracey Morgan Gallery (188 Coxe Ave., Asheville). For more information, call 828-505-7667 or see kirstenstolle.com.