Blacksmith learns to bend with the journey

Susan Hutchinson on her Weaverville farm with Grand Pyrenees livestock guard dogs Festus, left, and Esme.

Photo by Colby Rabon

Long before she fell to blacksmithing, Susan Hutchinson was going on dark journeys, her tools an obvious outgrowth of her energy. The artist remembers, in the early ’70s, selecting her black crayon and grinding out heavy marks with it until it disappeared. “Goth wasn’t a thing yet,” she quips. “My family just thought I was weird.”

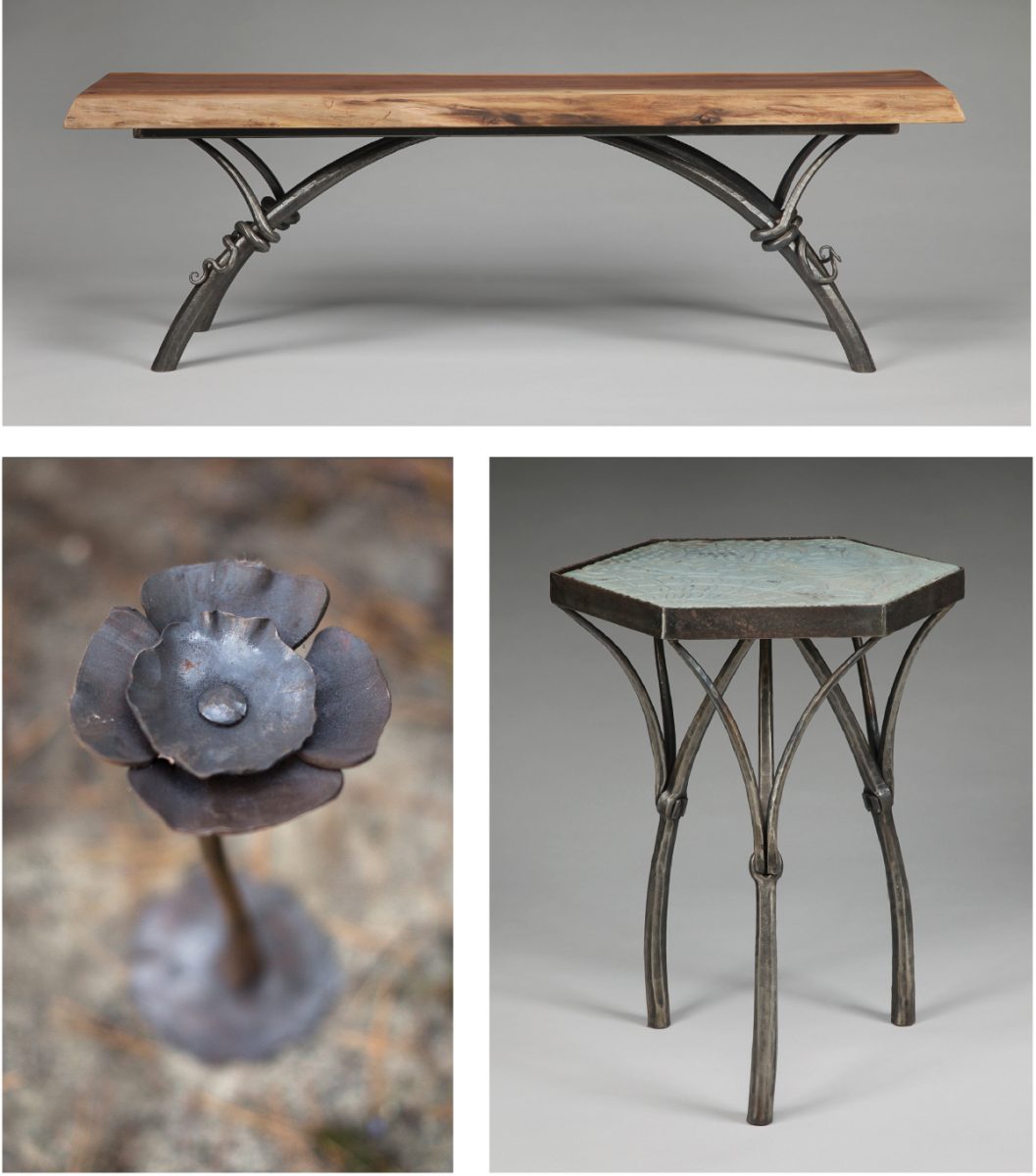

After she graduated with a BA in sculpture from Berea College in Kentucky, in 1988, and after she’d tried — and discarded — many other modes of artistic expression, she finally settled on metalwork. “Hot metal is plastic — like clay — in the way it moves,” says Hutchinson, “but it has the added interest of extreme tensile strength when it’s cold.” Imagine trying to create a large leaf on top of a thin, twisting vine using any other medium: “It wouldn’t stand up … and even if it did, [it would be] crazy-delicate and likely to break if you breathed on it. With steel, it works.”

Hutchinson’s pieces for home and garden.

Top photo and bottom right photo by Tim Barnwell; Bottom left photo by Colby Rabon.

Unlike clay, of course, hot metal cannot be shaped using only one’s hands. Tools, necessary to accomplish the task, therefore become an extension of the artist’s physical being — a phenomenon referred to as “body mapping,” Hutchinson says. She describes it as “a somewhat mysterious process where one’s mind senses the tool as part of the self. … That’s the place where the heat and the danger disappear … that kind of fluency is where the intuitive creative process can fly.”

At Penland School of Craft and John C. Campbell Folk School, Hutchinson acquired the skills and experience she needed to pursue her journey as a high-profile crafter. But she says her education continues with every new project she undertakes.

Photo by Colby Rabon

“I learn stuff every time I light a fire. Concepts evolve. The first draft of a product usually has this amazing spark of energy — and some horrendous fatal flaws. The trick is to resolve the flaws without losing that initial spark.” She says the processes can never be fully mastered, and the learning curve keeps things fresh. But the methodology, although difficult, becomes familiar, like working with an old friend. And because of that intimacy, she says, “manifesting an idea into a real object takes less struggle.”

Hutchinson makes objects ranging from small hooks to large architectural installations. Some combine form and function in dramatic ways, such as the 20-foot-long barrier shaped like a bank of trees she built over a client’s interior balcony, to prevent the homeowner’s grandkids from getting too close to the edge. “I like to make things that have some reference to living, mortal things,” she says. “The concept of life is [one of] time, of emergence and decay. Steel is really good at mimicking living things.” While she enjoys taking on private commissions, she’s quick to add that when clients want something not within her style, she helps guide them to an artist who might be a better fit. “There are so many fine blacksmiths in the region, and most of us have a specialty,” she comments.

Seven years ago, Hutchinson took a full-time position at Mountain Xpress. Ironically, she says, the day job has helped improve her artwork. “The problem of keeping the lights on and the bills paid can be overwhelming for any artist … I took the opportunity of this desk job to step back, reevaluate … generally overhaul my art life. My basic vision has always been good, but my implementation has needed improvement. I’m doing that better now.

“As I struggle less, more doors open, more ideas come, and weirdly, the blacksmithing I do is cleaner and just better.”

There’s a definite joy in the way Hutchinson goes about creating her art, which prompts the question: How would she describe her work to a child? Her answer reveals its own childlike glee: “I hit stuff. I play with fire. I get dirty. And I make lots of noise.”

Susan Hutchinson, Weaverville. The artist is a member of the Southern Highland Craft Guild (southernhighlandguild.org). Hutchinson will teach a week-long blacksmithing workshop, “Leaves, Vines, and Twiney Things,” from Sunday, Jan. 26 through Saturday, Feb. 1 at the John C. Campbell Folk School (1 Folk School Road, Brasstown, 828-837-2775, 1-800-FOLK-SCH, folkschool.org).