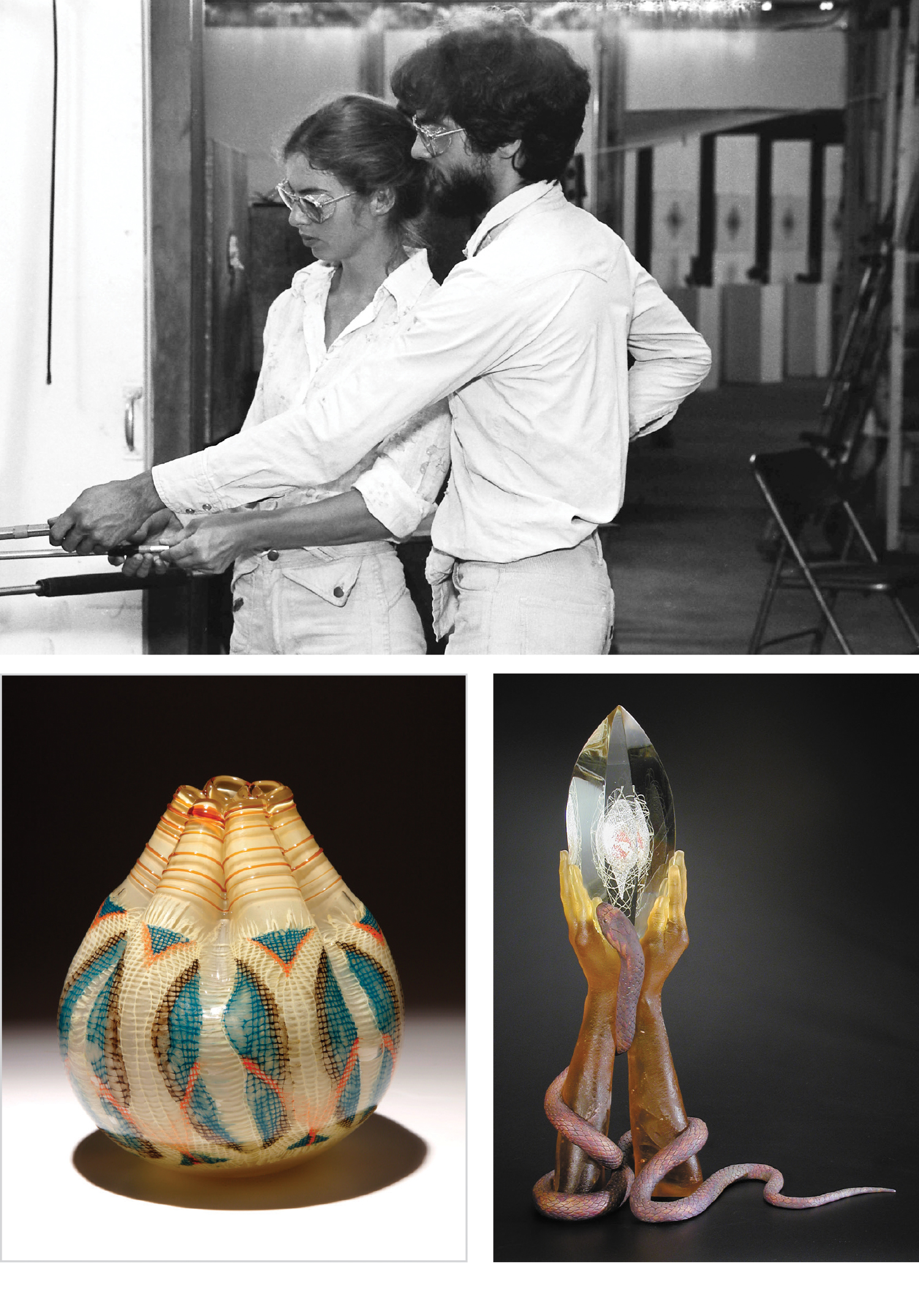

Portrait by Matt Rose

The launch of this summer’s blockbuster exhibit of outdoor sculpture by glass star Dale Chihuly at Biltmore House was the opening salvo. Now, a revival of interest in one of Western North Carolina’s artistic signatures brings the Asheville area’s “Summer of Glass” celebration to galleries and studios throughout the region.

It all seems bright and new. However, glass artists John Littleton and Kate Vogel have been intimately connected with the mountains’ glassmaking tradition for about four decades. John’s father, Harvey Littleton (1922-2013), established the first collegiate studio-glass program at the University of Wisconsin in 1962 (Chihuly was one of his students in ’67). Then the senior Littleton moved to the mountains of Western North Carolina to set up his own studio in the Toe River Valley, near Spruce Pine, gaining national recognition for his art. (He was attracted to the area by the Penland School of Crafts’ groundbreaking glassblowing workshops, first offered in 1965.)

John and Kate met at UWM, where both were enrolled in a pre-veterinary curriculum. But the school’s art department drew them together, where they studied photography, metal-working, and painting in addition to glassmaking. In 1979, they followed John’s father south and settled in Bakersville.

For both of them, creating with glass seemed a natural progression from their family history. In addition to Harvey Littleton’s legacy, John’s grandfather from that side of the family worked at renowned Corning Glass in New York State as its first PhD physicist. His grandmother, a photographer by hobby, was the first person to use Pyrex glass in the kitchen: her husband introduced her to an experimental substance from Corning, then called Nonex, used in signal lanterns. “A ceramic casserole she had only used twice broke, and she asked my grandfather to bring home some of that miracle glass,” John remembers. “He got a sawed-off Nonex battery jar, and she baked a cake in it. It worked well … Corning renamed the glass Pyrex for marketing purposes.”

Kate doesn’t reveal any rival stories but notes that her family likewise numbered “a long history of makers. … I have great-grandparents who were shoemakers, wagon-wheel makers, and my great-great-grandmother was a painter.”

Although both artists occasionally explore other genres, they’re most known for their distinctive blown and cast art glass, especially their pieces inspired by the human body. “We both worked with the human form in college,” John explains, “and around 1987 [in North Carolina] we started exploring working with faces and hands in glass. We often sculpt in wax, and some of our forms are direct life castings.”

Hands, opened to the sky as if in prayer, are the graceful structural supports for round or abstract shapes, inspirational text, or jewel-like elements. Faces gaze out from clear glass enclosures, or, more directly, as life masks. Other pieces are inspired by botanical shapes — leaves, reeds, flowers — delicately colored in hues that John and Kate often mix and melt themselves. “Some of the colors do change when they’re heated,” John says. “We make multiple tests to check how a color might change and react to the colors next to it.”

Most of their cast pieces are fired with the much the same “lost wax” method used in casting metal. Once a wax model has melted out through small holes in its mold, it’s replaced by glass heated to more than 1500 degrees Fahrenheit, fusing as it flows into the the form. Critical to the process is the cooling period, sometimes several weeks long, which must be carefully controlled to prevent flaws.

“With wax and casting you have more time to consider concept and form,” John explains. “Glass blowing is more immediate, and you have to make quick decisions.” Their blown-glass pieces are consequently more whimsical — softer and adventurously colored in shapes that recall sachets or even swirling evening dresses. They often appear paired or joined in larger groups, as though in homage to the couple’s almost symbiotic technique. “Our collaborative process becomes the most important thing,” Kate notes.

The couple’s largest, most challenging piece to date is a site-specific sculpture rising out of a fountain on the downtown campus of the public utility Spartanburg Water Systems. Sinuous vertices of sparkling-blue glass are mixed with steel, making the piece more technically complicated. Not only did it have to withstand the outdoors, “we also had to take into consideration the client’s desires and wishes, and make sure it fit the setting,” notes John.

John and Kate conduct a regular series of workshops at Penland School and lecture at art museums and colleges. Both have been involved in planning the Summer of Glass and will open their studio by appointment during the six-month-long event, as well as exhibit sculpture in Blue Spiral 1 gallery’s Glass Takeover show in downtown Asheville.

But whatever the project at hand — large or small, cast or blown — the couple’s cultural imprint is born from years of hand-in-hand creativity. “Ideas are what change the way we work,” Kate says. “They’re always what drives us in the studio.”

Kate Vogel and John Littleton (littletonvogel.com), Bakersville, will show pieces as part of the Glass Takeover exhibit at Blue Spiral 1, running concurrently with Asheville’s Summer of Glass event through October 26. Additional participating artists are: Kathryn Adams + Iron Maiden Studios, Dean Allison, Junichiro Baba, Rick Beck, Valerie Beck, Gary Beecham, Alex Bernstein, Robert Burch, Ken Carder, Victor Chiarizia, Shane Fero, David Goldhagen, Jan Kransberger, Robert Levin, Mark Peiser, Kenny Pieper, Stephen Powell, Robert Stephan, Justin Turcotte, and Hayden Wilson. For more information, see bluespiral1.com. For information about studio tours and events during Summer Of Glass, visit summerofglass.com. Chihuly at Biltmore runs through October 7; biltmore.com.