Madison County artist renounces portraiture to paint bugs and bears

Portrait by Evan Anderson

Nine years ago, Tess Darling felt trapped in her mind.

A Chapel Hill native who migrated to the mountains to play tennis at UNC Asheville, Darling had just graduated with a BFA and a résumé to match — a studio-assistant gig with the late River Arts District painter Jonas Gerard, and another with tape-and-sticker guru Stephen L. Lange. By others’ standards, Darling was doing the impossible: She was “making it” as a young artist in Asheville.

But Darling was too blinded by cognitive dissonance to celebrate her success. “I was painting figures and portraits, and I came to this realization that my work was vain. It was ego-centric,” she says. “I was so in my head — so stuck inside my own psychology — that I considered stopping painting altogether.”

Rather than put down the brush, though, Darling got behind the wheel. For a month, she traveled the country to clear her mind. Along the way, she would hesitate, stopping to observe clouds bruised purple by an impending storm or a sheer rock cliff frosted emerald by moss. That’s when she realized her folly: “I just needed to change my subject matter.”

In the years since, Darling has dedicated herself to capturing wildlife and landscapes, often en plein air. Her work is inspired by the life she witnesses on her 38-acre property in the Madison County community of Big Laurel. When she isn’t picking through feral bramble on foot, she’s observing flora and fauna from a two-story barn she turned into a studio amid pandemic lockdowns.

The space is rustic and rough-hewn. Without insulation, the painter relies on an insatiable wood stove to keep her warm during the colder months. But at least she’s in good company. “There’s an infestation of wasps, ladybugs, and mice that I’ve become familiar with,” she laughs.

Darling doesn’t mind the pests. If anything, they are her muses. After all, she describes her work as an attempt to challenge the human-centric nature of our society. “I want my art to serve as a reminder that there are other beings besides people,” she says. “I want to help others connect to the natural world.”

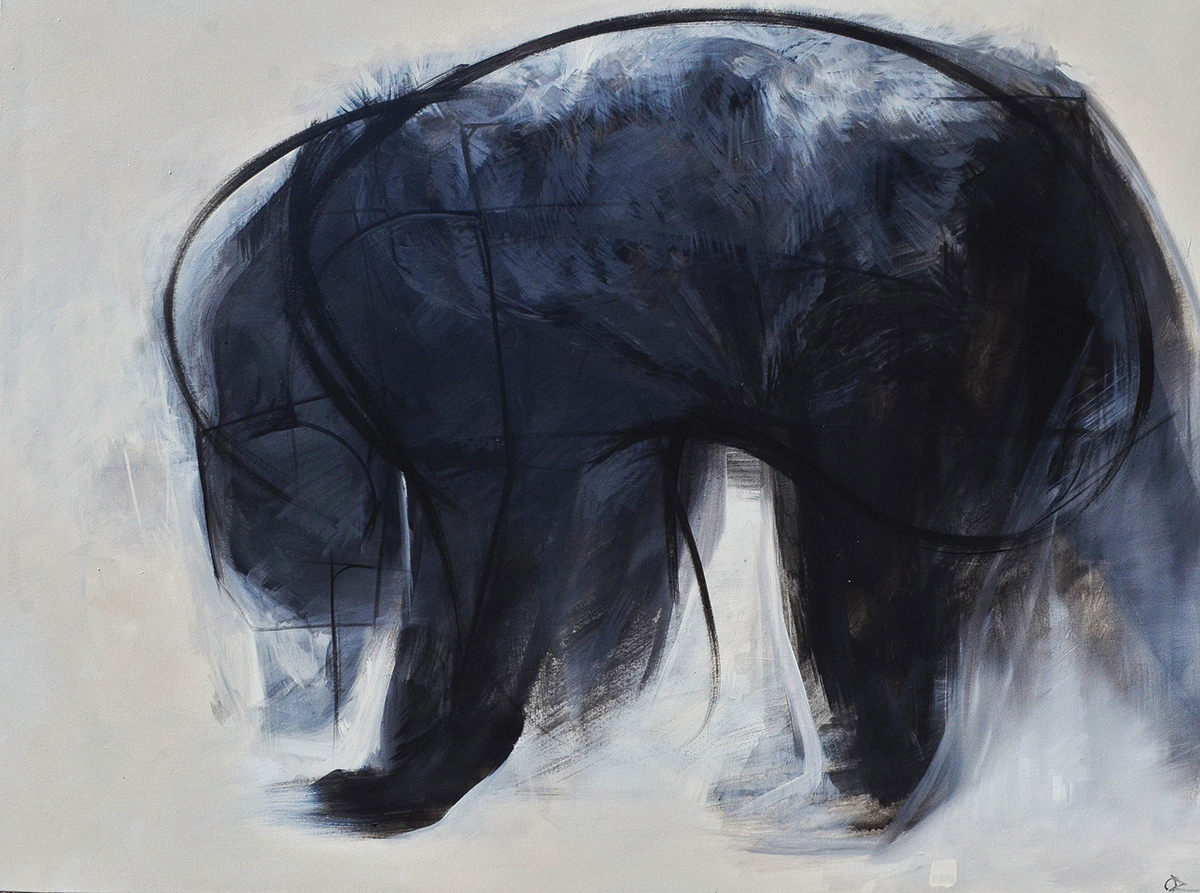

In short, Darling strives to capture a primordial view of Appalachia. A rainbow trout is seen up close, awash in iridescent pink and yellow, while the expression of a bugling elk in the Cataloochee Valley is celebrated in a subtle penumbra of gold. A coyote’s head is clearly delineated in blue, but the animal’s body is left in sketchy abstract.

If Darling can’t glimpse a lumbering black bear or furtive fox in real time — nature is fleeting, after all — she’ll reference trail-camera footage. This has been her artistic process since 2020, when she purchased the Madison County holding and moved her home (an aluminum camper trailer) to the site.

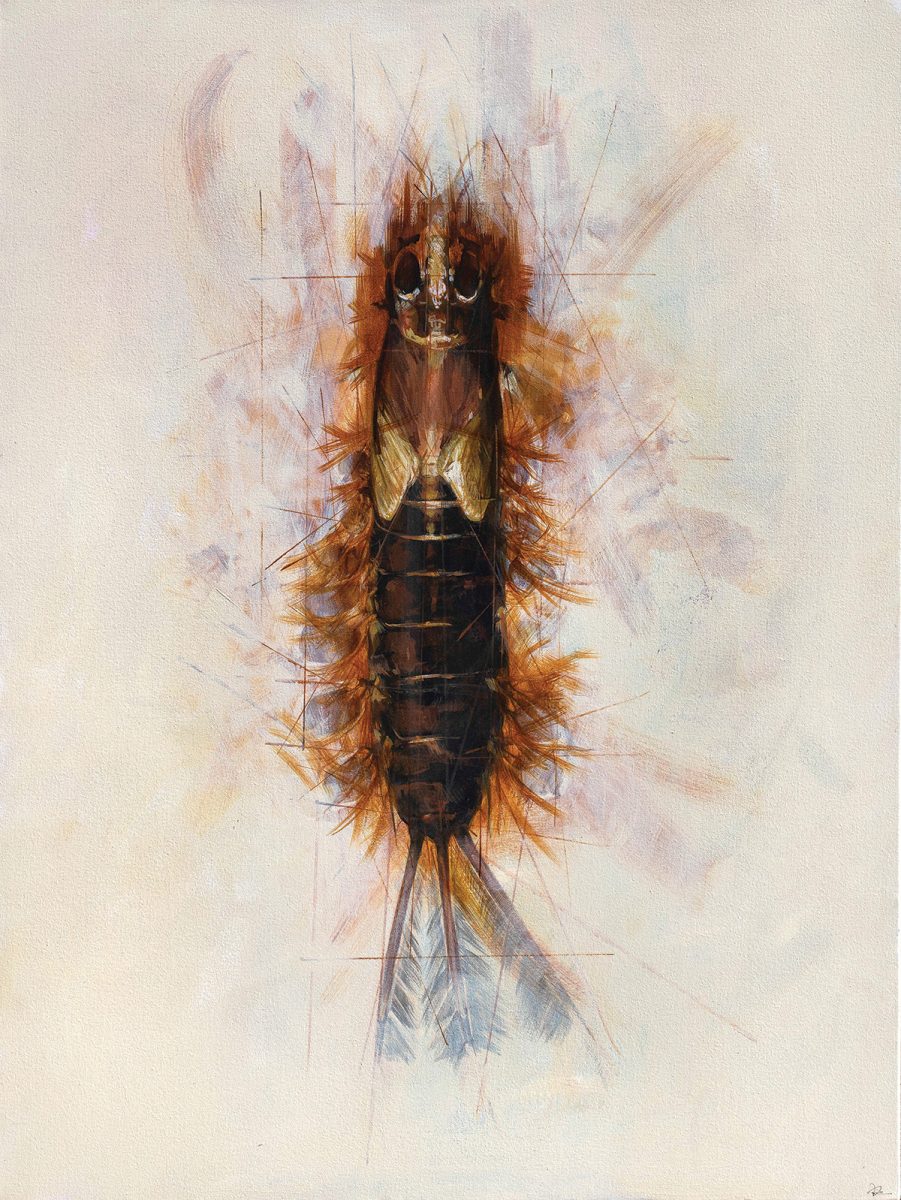

But after taking an aquatic-insect ecology course in Hot Springs last September, Darling’s creative process has become more hands-on. During the class, which was intended to introduce environmentalists to the taxonomy of certain insects, Darling collected mayflies and stoneflies from a mountain brook. She then observed the “ferocious creatures” under a microscope, noting their sharp structures and intricate patterns. Once back in her studio, she reproduced the insects in acrylic and ink.

The result is a mediation on ancient Appalachia — a look at “prehistoric dinosaurs” that have roamed the earth for eons. “A feeling of awe and fascination and curiosity is reflected in each piece,” says Darling.

Since that foray with antediluvian insects, Darling has made every effort to immerse herself in her subject matter. In November 2021, for instance, she spent 25 days rafting the Grand Canyon. When the surging Colorado River gave way to lazy bends, she would bask in golden light as it danced across the striated rock formations and try her very best to let “the environment fill up the world.”

That feeling of presence translates into the large landscapes she has created since. Looking at these paintings, one can’t help but feel transported, even a bit breathless.

“Painters in the 18th and 19th centuries called that feeling the ‘sublime,’” Darling explains. “It’s the sense of danger and vulnerability — the sense of living in the world instead of being shut away from it.”

Tess Darling, Madison County. Darling is represented by Mark Bettis Studio and Gallery, 123 Roberts St. in Asheville’s River Arts District, markbettisgallery.com. To learn more about Tess Darling, visit tessdarlingfineart.me.