Portrait by Matt Rose

Growing up in Brooklyn, Asheville artist Cleaster Cotton remembers the day her mother brought home an injured bird. “My mother was an activist for children and for animals,” Cotton says. “She came home with a coffee cup, and she had a little bird in the cup. Its wing was broken, so she attached a popsicle stick to the wing. After hopping around on the kitchen table for a few weeks, it just flew away.”

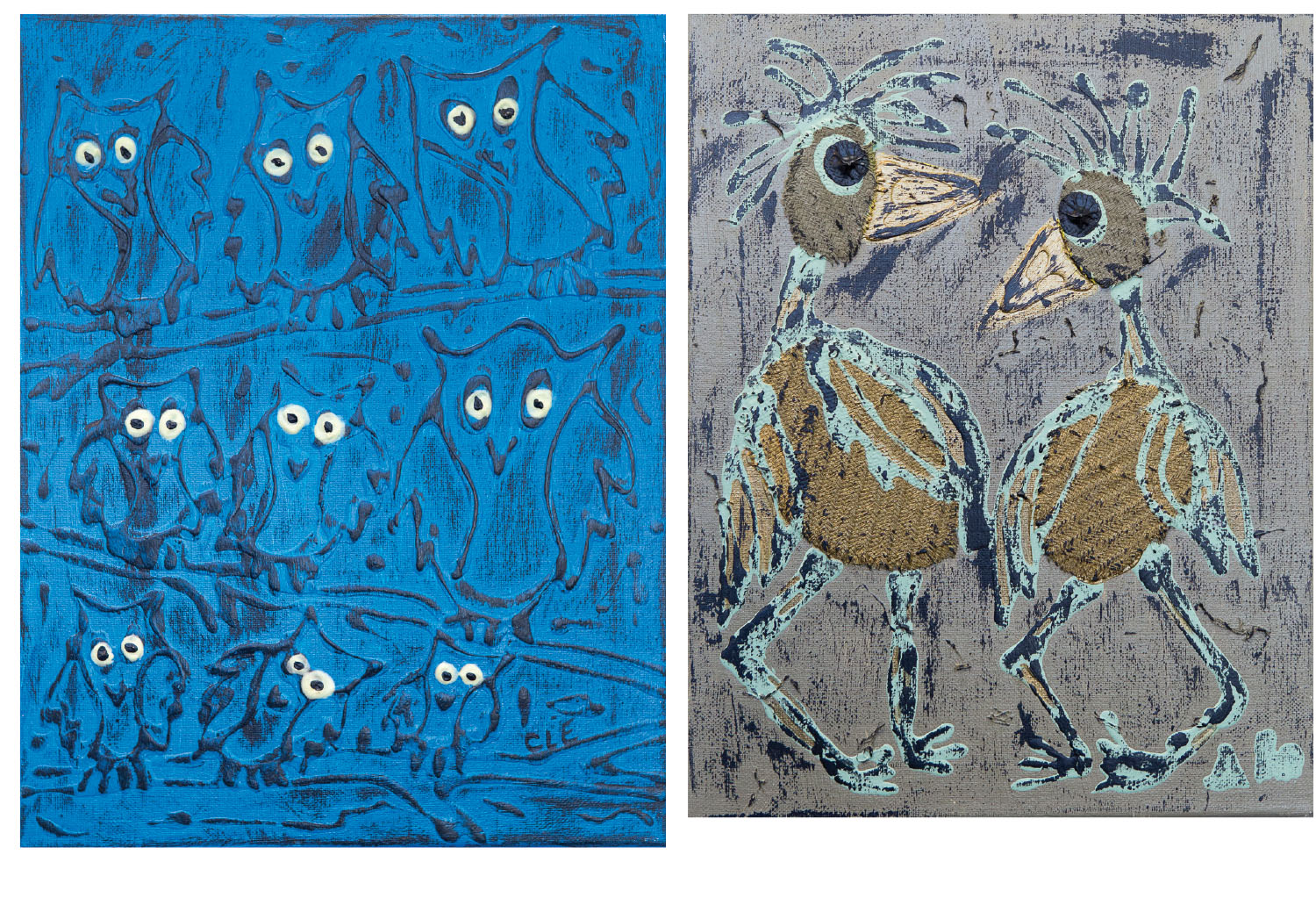

Now, an entire flock of colorfully rendered birds will populate Cotton’s show “Winged Narratives: A Social Study” at Asheville’s Lounge Gallery on Coxe Avenue. Playfully spiritual and brilliantly rendered in acrylics blended with fabric and other collaged media, the birds tell a story of survival and social cohesion while asking viewers to find their own place in the natural order. “Birds carry a lot of symbolism for many cultures,” Cotton says. “One of the reasons for the exhibit is I want people to love birds and want to protect them and their environments. I want them to know that birds have a connection to our own existence.

“Birds are essential in keeping a balance in nature,” she explains. “By eating pests, they are agents of insect control. They are pollinators. And if we watch these harbingers closely enough, they will signal weather changes, changes in seasons, and will inform us of shifts in the ecosystem.”

Raised in New York by parents who emigrated from the Carolinas during the great post-war migration of southern African-Americans to northern urban centers, Cotton says backyard mud sculptures were an early childhood experiment in color and shape — brightly painted with the juice of berries and textured with bits of flowering plants. It was her mother who encouraged Cotton’s first attempts at drawing. “When I was about five years old, I remember her sitting at the table with a brown paper bag, drawing some of the images from comic strips in the newspapers,” she says. “It seemed like magic to me, and I said I wished I could do that. She said, ‘You can,’ and she said everything is a shape. My mother showed me how to look at the world as a collection of shapes, and how you can draw lines to connect them. A Cubist was born …”

But her work long ago broke free of such genre restrictions, drawing from a Fauvist palette for vibrant and unusual colors, from Structuralist idioms for compositional energy, and from Outsider art for material texture for her landscapes, still lifes, and portraiture. Flowers seem to have sprouted from the ground only moments ago, human figures dressed in blues, yellows, and reds cavort against pulsating backgrounds, a fiery-red sun extends its arms to touch a deep blue sea and soothing green earth.

Cotton identifies herself as a “Nubian-American contemporary primitive painter,” a tag combining her deeply felt connection to both family and art history. “My DNA reaches back to my Nubian ancestors,” she says, referring to the ancient African culture of southern Egypt. “They built pyramids. My Dogon ancestors mapped out the solar system with no modern technology, and I call upon that energy … in the contemporary world.”

Each of her pieces is born slightly differently, some beginning with preliminary drawings and others coming to life directly on canvas, paper, wood, or tarpaper. “Sometimes the inspiration is so visual that I have to put the paint right on the medium,” Cotton says. “Other times I sketch the paintings out ahead of time, or start with an underpainting and build up the surface with textures like cloth or burlap.”

Nor is her work confined to canvas and brushes. Her paternal grandfather inspired Cotton to take pictures as well as paint them. One day, she remembers, while visiting him in his large, early-20th-century home in the Bronx, with its high ceilings, ornate plaster moldings, and tall windows admitting abundant light, “he brought out his camera and put it around my neck. I looked down into the viewfinder and everything was upside down. I fell in love with refraction!”

Today, Cotton’s nature and architectural photography is much prized, particularly a series she produced of the interior of Atlanta’s landmark Sears Roebuck & Company Building, before its conversion to the Ponce City Market. The project, sanctioned by Atlanta’s Bureau of Cultural Affairs, captured the building’s hidden spaces — where, Cotton says, she “saw jewels and shapes in the light.”

Her artmaking is a way for her to follow in the footsteps of her mother’s social activism, with a portion of all sales donated to school and social programs that empower children through academics and the arts. Cotton frequently works with the Asheville City Schools Foundation, UNCA, and LEAF Community Arts. “It was so fabulous that my mother encouraged me,” she says. “She had a genuine care and concern about humanity.” Her mother babysat children for working people in the neighborhood, and sometimes temporarily housed abused and neglected kids. She was also known for attracting wildlife and taming neighborhood dogs considered vicious by others.

“She intuitively knew when someone needed something and made sure they received it,” says Cotton. This included providing arts enrichment and game-based education. “Some children had to be carried out kicking and screaming when their parents would come to pick them up. No one ever wanted to leave the love in our house.”

Cleaster Cotton’s “Winged Narratives: A Social Study” runs in the Lounge Gallery at The Refinery Creator Space (207 Coxe St., Asheville Area Arts Council on the South Slope, ashevillearts.com) through Friday, Jan. 25, 2019. “Asheville Through Brown Eyes,” a group show featuring Cotton’s work and that of seven other African-American artists from Buncombe County, shows at The Thom Robinson and Ray Griffin Exhibition space (ashevillearts.com/exhibitions/asheville-through-brown-eyes) through Friday, Jan. 11, To learn more about Cleaster Cotton and her work, visit cleastercotton.com.