Portrait by Paul Stebner

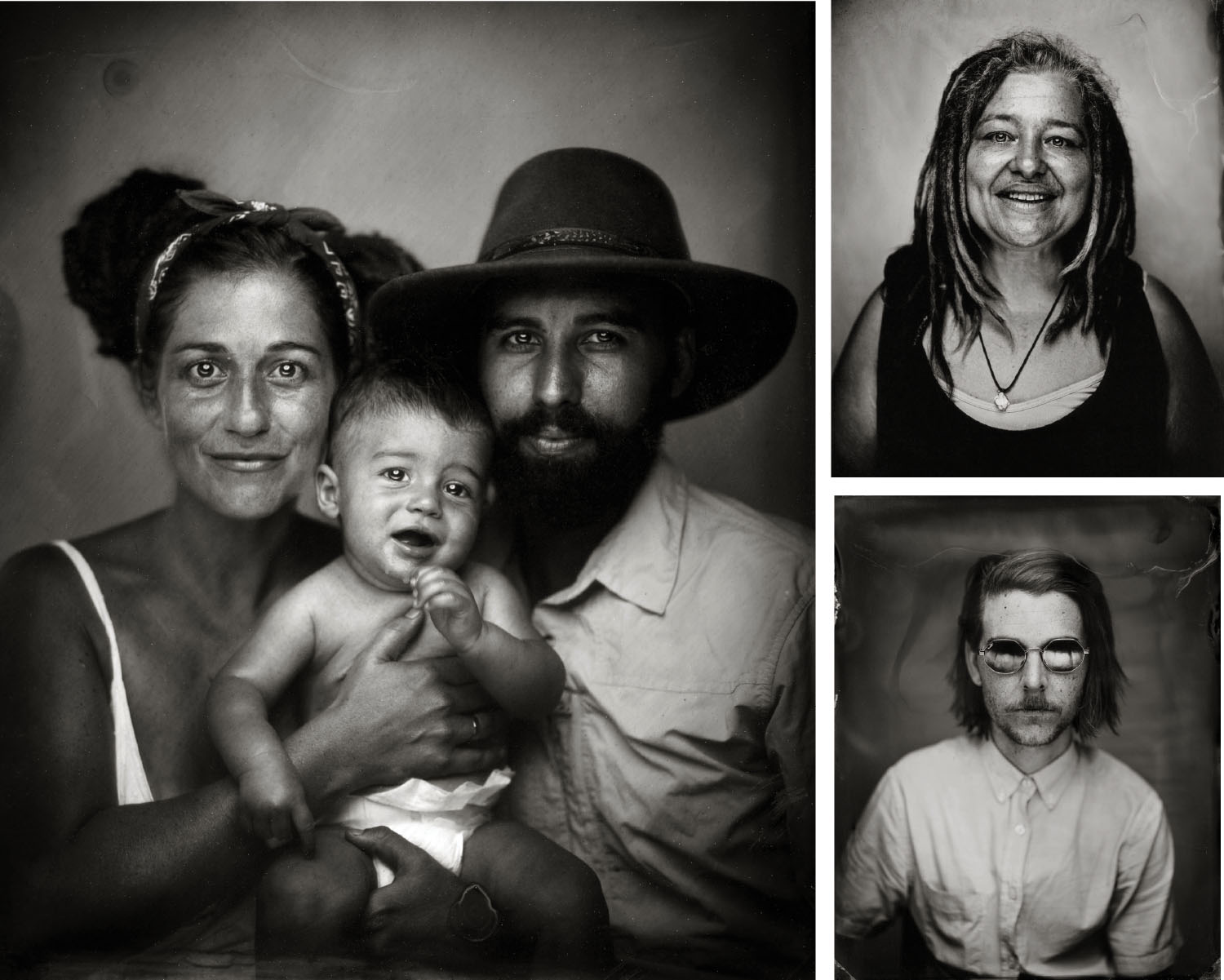

Tammy died seven times before she sat in front of Rianne Farris’ antique box camera. “I had asked if I could take her tintype photograph,” Farris says. “She was a person who was born into a life of trauma and has suffered greatly. She was telling us her experiences of crossing over and how she has been changed as a human from going to the other side.” Farris explains how powerful her time with subjects becomes, as she she spends time adjusting them, explaining the process, and simply getting to know them.

Farris is co-owner, with life and business partner Jonathan Sherman, of Ancient Kind, a tintype and cyanotype studio that started out of their car a year ago in the Chicago area, where they previously managed darkrooms. Sherman and Farris now live in Maggie Valley and are converting a bus into a mobile tintype studio that they’ll eventually park in Asheville.

Cyanotypes are contact or “sun” prints that result in an ethereal blue color (hence “cyan”). Sherman calls tintypes, or wet-plate collodion, as the process is also known, “the most challenging yet rewarding pursuit of art we have embarked on.”

When one thinks of tintype photos, it’s those stiff portraits from the 19th century that seemingly took forever to achieve. In them, subjects are stern and unsmiling. If their eyes come into focus at all, the result is a spooky, thousand-yard stare. The frame is haunted by ghostly images of children or pets passing through the field during the exposure.

Things are different these days. For one, a strong flash accomplishes the exposure in a moment, and subjects’ eyes seem to pierce through the surface of the photo, deep and engaged.

“Although this process yields such striking results, tintypes will make you earn them,” says Sherman. In fact, the pair allows 30 minutes for each image to develop. The coated aluminum, made onsite, is then loaded into a camera so old there’s no shutter. They prepare subjects for what’s about to happen, then duck under the cloth. When the lens is removed and replaced, the flash is so bright subjects can feel the heat on their faces. There’s only one chance to get it right.

But another magic moment happens when the image floats gently into the fixer and subjects watch their image reveal itself. There are often tears, Farris says. She remembers the tender moment a newly divorced man saw the image of himself and his daughters. It became “this time marker of something that was very hard but also very sweet,” she explains.

This is the moment when the “artifacts” appear. These imperfections arise from the chemical process that turns the aluminum into film. Because of them, subjects may seem to rise out of darkness or have smoky plumes over their shoulders. Edges are sometimes rimmed in bubbles.

The images don’t have to look like that. In fact, Farris and Sherman have learned to make very clean images along the way — but they prefer the alchemy of artifacts, and the magic they conjure.

Ancient Kind sets up outside Green Man Brewery (27 Buxton Ave. on Asheville’s South Slope) Thursday and Friday nights from 4-10pm. For information about Ancient Kind’s fall and winter classes and events, see ancientkind.com.