Weaver uses a magnifying glass to make her intricate patterns

Portrait by Clark Hodgin

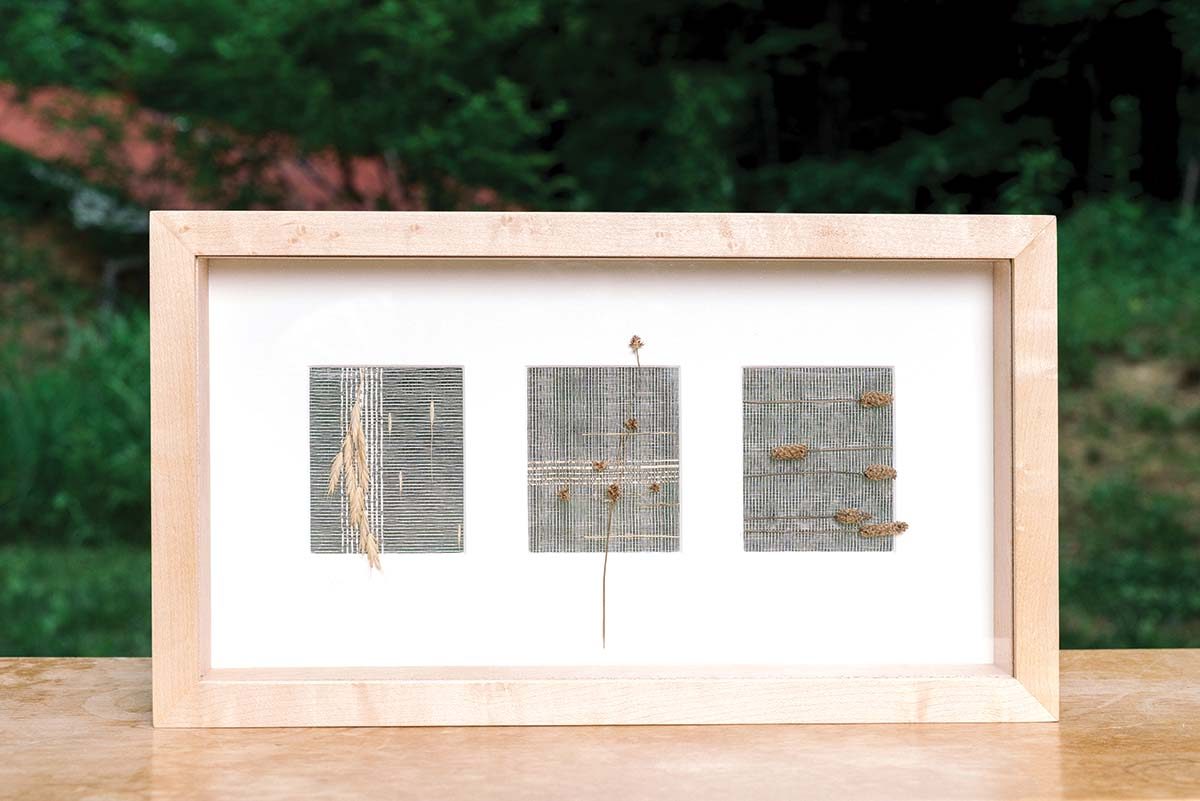

When Vicki Essig arrived in Western North Carolina more than two decades ago, the first thing that struck her was how different the Blue Ridge mountains were from the arid austerity of the Rockies, where she’d grown up. “I had to learn respect for these older, softer mountains,” Essig remembers. Her deep absorption of a new landscape has resulted in a distinctive body of assembled art that draws not only from the physical landscape but from the cultural fabric of Appalachia. Stones, fragments of wood, leaves, and the spiked buttons from gum trees are interwoven with silk and other matrices as a visual paradigm of a mature ecosystem protective of its mysteries.

The mountains also introduced her to her partner and fellow artist Daniel Essig, whom Vicki met some 10 years after settling here. Vicki remembers the morning Daniel presented her with a bright-orange newt he had foraged from the damp woods surrounding their cabin. It was

one of the many discoveries made by a couple who share an attachment to art rooted in nature.

“When I first moved here, my only creative outlet was cooking,” Vicki recalls of those first days in the Blue Ridge. “Exploring cookbooks, making lists. Preparing all day for a meal is still one of my favorite things. It was the first way I felt proud when I said, ‘Look, I made this.’” But the next-door neighbors turned out to be the artists Kate Dwyer and Myron Gauger, who encouraged further explorations of creativity. “They taught me where to hike, about plants and gardening, how to live as an artist and to live with art,” Vicki says. They also introduced her to Penland School of Craft and its classroom and studio opportunities, which would come to play an important role in her growth as an artist.

Photo by Steve Mann

In fact, the Essigs were married at Penland 13 years ago, and recently settled into a home near the school. On the banks of the North Toe River and across from the landmarked Penland Post Office, their home is a front-row seat for the mountain seasons that so influence their work. “The winter was beautiful,” Vicki says of the past year. “We could watch the river along with geese, herons, and a bald eagle. Now we’re cocooned in a chlorophyll jungle.” Both artists teach and continue to take classes at Penland.

One of Vicki’s earliest mentors was the weaver Catherine Ellis, a longtime faculty member at Haywood Community College who would later become known for her adaptation of the traditional Japanese weaving technique Shibori for American weavers. “She has inspired me for over 20 years,” Vicki says. The influence is evident in the wonderfully intricate patterns against which she sets her botanicals. The patterns Vicki weaves are so delicately rendered that she uses a magnifying glass while weaving on one of the two antique looms that take center stage in her studio.

“People say to me that they wouldn’t have the patience to weave, but for me it’s the contrary,” she says. “I find it meditative. I feel centered there.” She raises silkworms herself, fascinated by their ability to weave even outside of a cocoon to produce “flat silk,” spun out on a flat surface. “I don’t use it in my work at present, but I did want to learn my materials, so that’s how I started raising silkworms,” Vicki explains. “Making them spin flat is just a cool thing.”

Producing complex patterns on a loom necessarily requires planning, but much of the rest of Vicki’s process is intuitive and organic. “I am a very ‘let’s see if this works’ kind of person,” she explains. “I make a lot of train wrecks, which are a great teaching mechanism for me.” But the result is work faithful to the randomness of nature, as if each piece had been found intact and already formed. It’s about texture and shape, harmony and contrast; the tranquility of green mountains against blue sky, the warmth of wood, and our deeply embedded bonds with nature and with each other. Equally nurturing is the artistic symbiosis with Daniel, of whom Vicki simply states, “He taught me to see. He is a most amazing teacher.” Some of her work incorporates objects and materials shared with him, particularly pages from old books or manuscripts which form the work for which Daniel is most known.

“Creativity, community, and confidence are three of my favorite things. The creativity of nature, my own creativity and of those around me,” Vicki says. “Someone once told me that what I made was pretty, but she thought I had more to say. I think I’m still looking for what I have to say.”

Vicki Essig, Penland. Essig’s work is shown locally at Penland Gallery at Penland School of Craft (penland.org). The show “Silk & Spine,” featuring Vicki’s woven pieces and Daniel Essig’s sculptural work, runs at Blue Spiral 1 Gallery (38 Biltmore Ave., Asheville) through Saturday, Aug. 31. 828-251-0202. www.bluespiral1.com. She’ll also have work in the “Paper-Centric” exhibit at the Toe River Arts Council (269 Oak Ave., Spruce Pine) Saturday, Aug. 10 through Saturday, Sept. 14. (Additional venues: Blowing Rock Art & History Museum and David McCune International Art Gallery in Fayetteville.) www.vickiessig.com.