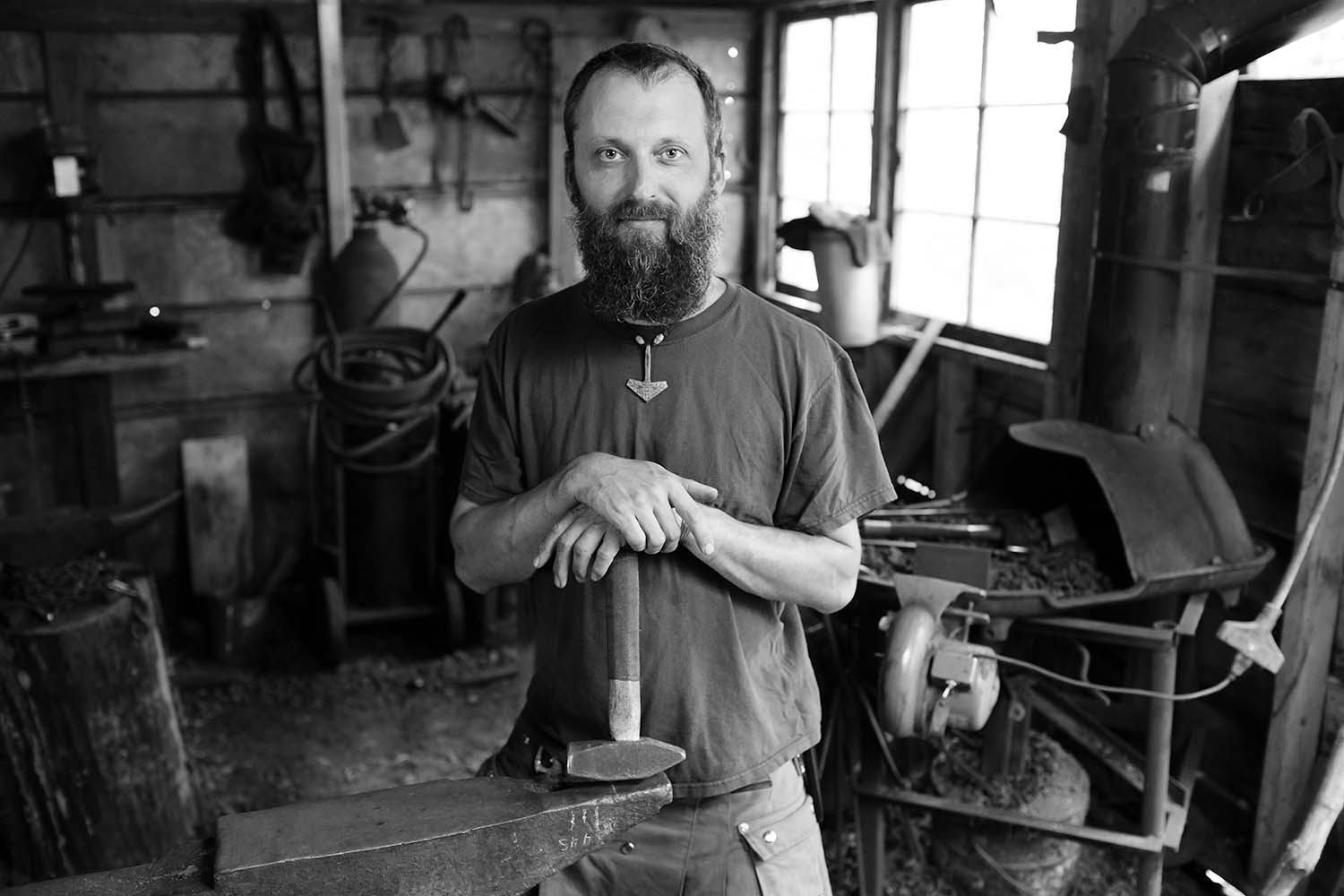

When Matthew Shirey was 19, he phoned his father and told him he had found his life’s calling: to become a blacksmith. “You’re never going to make a living as a blacksmith,” his father told him.

“He was right for a long time,” says Shirey, now 39 and owner and operator of Shira Forge in Sylva, where he produces hand-forged knives, axes, and kitchenware. Though for many years Shirey’s blacksmithing was relegated to hobby or part-time status, he’s been working with his hands since he was 20 — as a carpenter, welder, and shop teacher. Now, he says, “I’m finally paying the bills” with forging alone.

His kitchen tools include frying pans, woks, spoons, and spatulas, and are appropriate for any style of cooking — on an indoor stove or a campfire. “I do a lot of cooking, so it was natural to get into kitchenware,” Shirey says. “That’s always been the appeal for me—making the object and then using it to make something else.”

As a kid, Shirey was drawn to history and primitive tech — what he calls “the old ways of doing things.” The 18th and 19th century held particular fascination. “Like most boys that age, I had an obsession with knives and fires,” he recalls. “That you could stick a piece of steel in fire and a make knife out of it was pretty exciting. That led me to blacksmithing.”

His work continues to be influenced by that era, especially early Appalachian culture (Shirey grew up in Clarion County in Western Pennsylvania before making his way to Sylva). “People in the mountains didn’t embellish a lot,” he notes. “There’s real beauty in something that is simple and functional. It’s graceful. If it works well, that makes it more beautiful.” Still, he’s not turning out exact reproductions: “I’m adding a slightly contemporary touch.”

The process begins with raw steel. A frying pan, for instance, is cut from a sheet of carbon steel. “Then I fire up the forge and start hammering,” Shirey says. After the pan is formed and the handle riveted, it spends an hour in a 500-degree oven, which draws out dark-blue tones and creates surface oxidation to prevent rust. He can complete a frying pan in two to four hours, depending on the size, while knives can take up to a week or more.

Shirey teaches several blacksmithing courses at Haywood Community College, and he has started to pass the craft on to his sons, ages eight and four, as well. “Sometimes I hope they choose a safer, more practical route,” admits Shirey, though he’s unlikely to dissuade them.

“I just love that I have the chance to play with fire every day. I’m mesmerized by the process — heating metal and turning it into something functional. I never get tired of that.”

For more information, see shiraforge.com. Matthew Shirey’s next course at Haywood Community College, on forging jewelry, begins October 20 and runs for six weeks (haywood.edu).

I have a hunting knife he made. It is simple and beautiful in a rustic way. He makes a quality product. Even my hillbilly neighbor was impressed with the quality of steel in the blade.