Clinical psychologist Dr. Carol Brothers often mentions the views of Beaver Lake she and her husband Dr. Fred Klappenberger, a cyber-security expert, will enjoy from their home-to-be in North Asheville. But it’s an island inside the house — the slab of granite in the kitchen — that really stirs up her aesthetic.

The anchoring countertop is “black and white and taupe, very modernistic,” says Dr. Brothers. “It makes a big statement.”

The couple has been “doing ultra-modern” for more than a quarter century, beginning in Annapolis, Maryland, where they enjoyed their first avant-garde home. When they moved to the southern mountains, they sought the Cane Creek area first, but found it too far from Asheville attractions and Brothers’ downtown office. Then, for a while, they rocked the winged-roof penthouse at 12 South Lexington, before selling that space and finding the perfect happy-medium parcel in Lakeview Park.

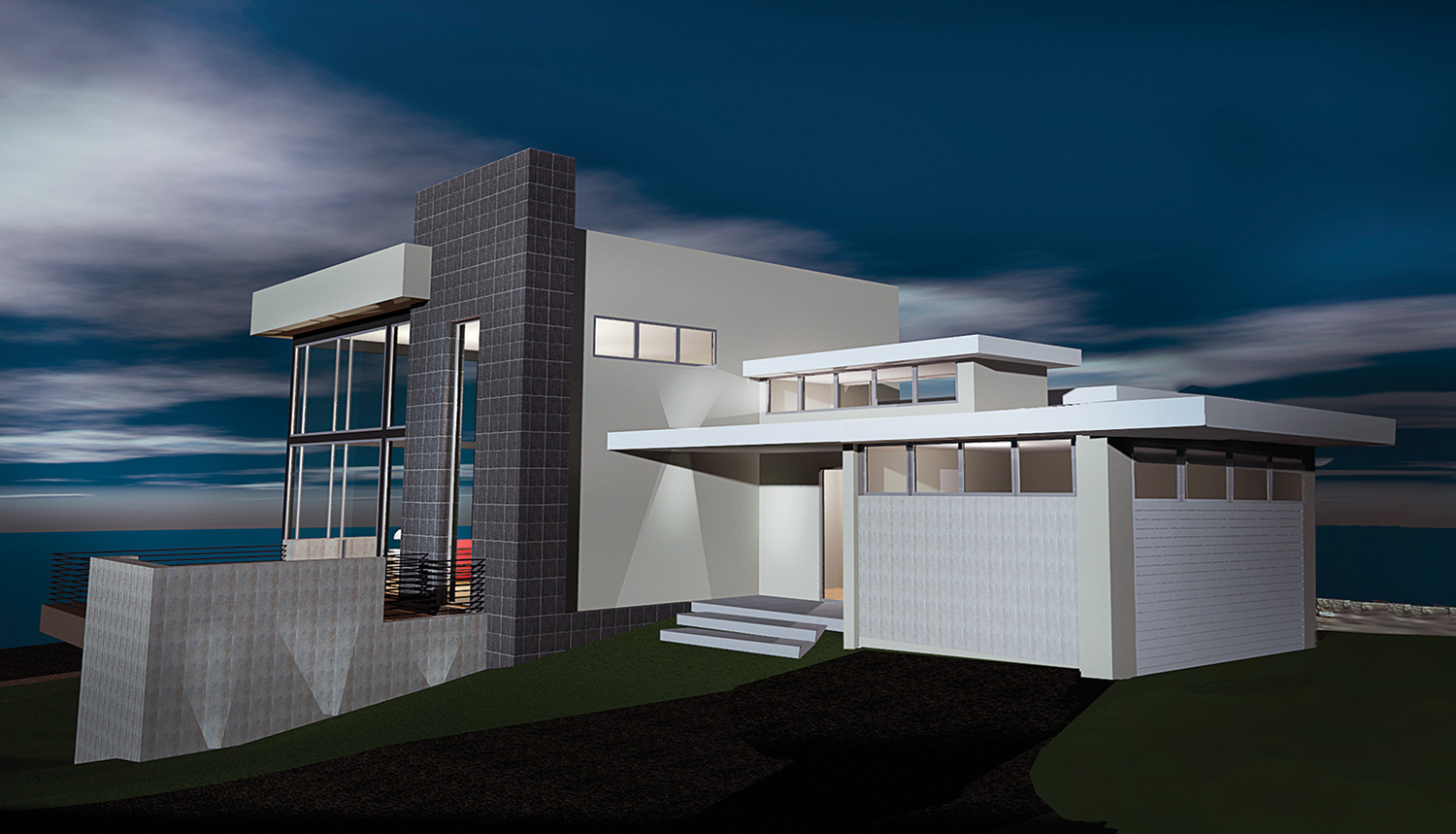

Though it looks out on a calendar-worthy vista of water and mountains, the property is 100 percent urban. Perched at a smart angle on an efficient lot, the 3,200-square-foot, four-bedroom, three-and-a-half-bath house — projected for completion in early 2017 — will sit high enough to hide the bustle of Merrimon Avenue from inside, while its inhabitants can still make use of that busy thoroughfare for a swift commute.

“If it were further into the depths of the Lakeview community, among some of the traditional Arts & Crafts and older homes, the house might stick out,” admits Dr. Brothers. Because it faces the street, though, “I think we’ll do fine with having unusual architecture,” she says.

On the other hand, principal architect Robert Griffin points out that one of Asheville’s classic examples of high-end progressive architecture, the 1940 Weizenblatt House designed by Bauhaus alum Marcel Breuer, is also in Lakeview. With project manager Jon Moore, he reaches for a new definition of modern that doesn’t just acknowledge the now 100-year-old hallmark of residential “contemporary” — basically any non-gabled, flat-roofed structure — but instead favors the newest, warmest iterations of the genre. These are buildings designed not just to call attention to their own lines, but to honor the landscapes they inhabit.

A thick-walled, striking monolith of dark porcelain tile distinguishes the approach of the Brothers/Klappenberger home, re-emerging within the primary living area to establish the building’s literal and figurative threshold. But the roof plane is broken up in many sections — like the profile of the local mountains themselves, points out Moore. And the choice of cozy earth tones softens sharp angles. “We’ll be using black, dark taupe, beige stucco,” says Griffin. (Red trim inside acknowledges the couple’s gutsy red-leather sectional sofa.) These hues are a definite way, he jokes, “to keep it from looking like it belongs in Miami Beach.”

“We’re really in a new generation [of modern],” muses Moore. “Not ‘contemporary’ or ‘international’ anymore … maybe ‘international revival.’”

“Or ‘neo-modernist,’” says Griffin. The main level of the home features a ceiling that reaches up to the second story. Two sides are clad entirely in glass — and not just for the sleek look of the material itself.

“The primary reason for all the glass is to capture the view,” he explains.

“The interior will ‘live’ like it’s outdoors,” adds Moore.

Brothers, who says she is “not a humidity lover,” is excited about the great room and its climate-controlled transparency to nature, calling the expanse of glass “very modern, very simple, with great clean lines … this will be an easy place to live without a lot of fuss or distraction.”

However, it takes keen planning to execute this kind of au courant architecture. Dazzling as all the glass is, abundant glazing that makes a house more vulnerable must be balanced by a substantial structure (Moore notes the work of Medlock and Associates Engineering on the home). And any barrier to “universal design” — i.e., stair-free accessibility, important in a retirement home — has to be reconciled with the demands of the lot.

Once the structure is braced, though, the inviting canvas allows many abracadabra moments. Her beloved kitchen island is a definite “wow” piece, and Dr. Brothers also talks about the freedom of smooth, plain, well-lit walls that will act as a gallery to display the couple’s modern-art collection, including many large paintings. A favorite quirky furniture score is an Art Deco bar by Dakota Jackson, the renowned designer who began his career as an illusionist. The piece is inspired by a traditional magician’s table — sawed-in-half assistant not included.

The psychologist credits the “exacting professionals” at Griffin Architects, “amazing” builder Dan Hensley, and two “fabulous” interior designers, Edward R. Stough of Baltimore and local kitchen/cabinet designer Christy LaDue, for working their own magic to unite all the elements. The result, she says, “is simply thrilling. You feel an excitement from the moment you enter the house.”

For more information about Griffin Architects, call 828-274-5979 or see griffinarchitectspa.com.