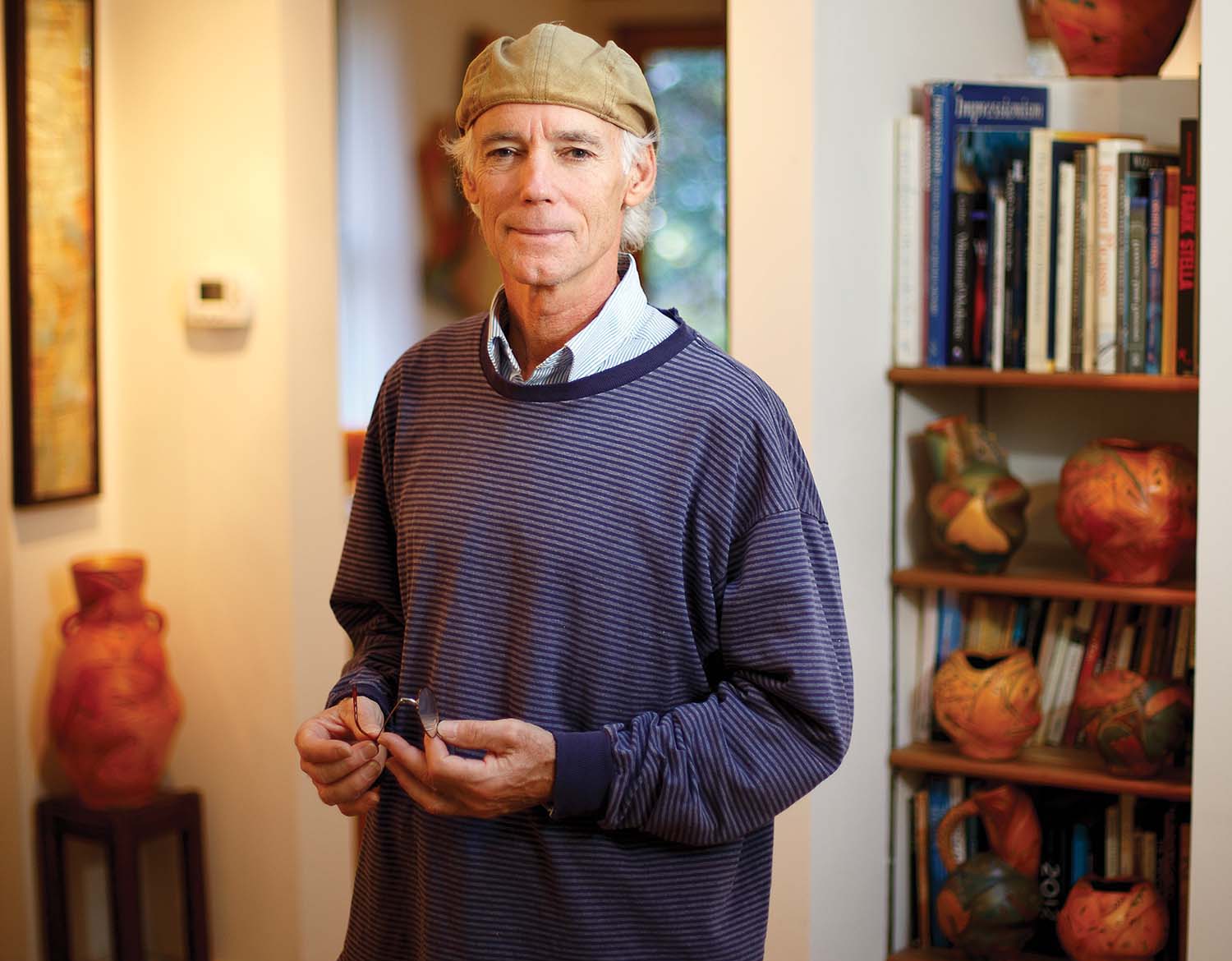

“More than looking at art,” says sculptor George Handy, “I listen to it. As far as I am concerned, a lesser piece of art is a mute piece.” It’s an artistic tenet he applies to his own creativity. “I stare at the clay and wait to see what it wants,” he explains. “If it costs me more time than fits the budget, that’s okay. Art is not art unless it is brought to its fullest potential.”

Over most of his professional life, Handy has concentrated on making pottery. Among the most popular items have been his mugs and, when he felt he could no longer improve on their design, he turned to casting them. The change to casting, he says, also became necessary when he began suffering from carpal tunnel syndrome. “I could no longer throw 80 pieces per day. So slip casting and focusing on painting the surfaces was my only option.”

His father was a Hall of Fame thoroughbred trainer, and Handy says he was about six years old when he made his first pots from the poultice his father used to reduce inflammation in the horses’ legs. “My sister and I would make pinch pots and roll the clay with a dowel, creating abstract animals we would line up along the barn walls to sun bake. The jockeys would sometimes buy them for a quarter,” he remembers. Having never read books about working with clay, Handy says he believed in his naïveté back then: he thought he’d invented these methods.

His interest in clay never waned. When he was 13, Handy constructed his first studio, and by the time he got to college, he could throw pots almost as well as the ceramics teacher. As a result, he decided studying writing would provide a better educational background.

He put himself through college by managing a bike shop, where he built racing wheels in the daytime and made teapots late into the night. Handy graduated from Plymouth State College in New Hampshire in 1976 with a degree in English education with a focus on creative writing. Even with his lifelong career as a sculptor, George says, “I still write fiction and poetry each day — my greatest joy.”

After making an estimated 30,000 mugs, in addition to bowls, teapots, tiles, and other small pieces over his career, Handy more recently began working on a much larger scale with his public and corporate art installations. He jokes that, as Baby Boomers started to age, he needed to make larger works “so even us old ones can still see and appreciate the subtle.”

Handy says he “very much loves” the process of creating public art. “My goal is to make wall sculptures that inspire people to talk about them. That’s a big pursuit because, unless the piece is damn good, it fails.” Always evolving, he has started including holographic surfaces, which cause the images to appear to change when viewed from different angles.

He describes one such public piece that was commissioned for the Charlotte Fire Department. It was originally to be clay, “but as it developed,” says Handy, “I realized clay was not right for this project. So I researched and designed a deeply carved, sandblasted series of six glass pyramids, which I feel is the best of my sculptural pieces.”

As viewers come into the room, they are met by a scene of ladders, hoses, and other images depicted in fiery oranges and reds. As they continue along the sculpture, other images in blue and teal emerge, reflecting a watery calmness. Taken together, they represent the wide range of heroic work performed by firefighters.

Driving his artistic success, from his smallest works to the largest, is an insatiable curiosity. “My work remains alive for me because I’m regularly challenging the designs to change, adapting imagery and color, (and traversing) from dinnerware to carved glass and large public art commissions.”

In 2008, a car crashed into his studio, reducing to shards years’ worth of work. Where others might despair at such a loss, Handy saw a chance to establish two new workplaces: a studio in Weaverville for his pottery and another in Woodfin where he is able to create his larger pieces.

In all of his works, big and small and regardless of medium, Handy holds fast to his self-imposed discipline, working on them until they discover their voice.

“It’s blasphemous,” he says, “to send a mute piece of art out into the world.”

George Handy welcomes visitors at his Woodfin studio, 2000 Riverside Drive, Studio 5. For details, visit georgehandy.com or email georgehandy6@gmail.com.