Illustrator embraces the simple life via deep ecology

Jacqueline Maloney draws from a time before Internet.

Portrait by Rue Sakayama

In a world glued to screens, Yancey County artist Jacqueline Maloney sports a flip phone and a landline, checks e-mail only twice a week, and spends mornings nurturing her garden as opposed to her Instagram following. This approach “came out of remembering a time before Internet,” she says.

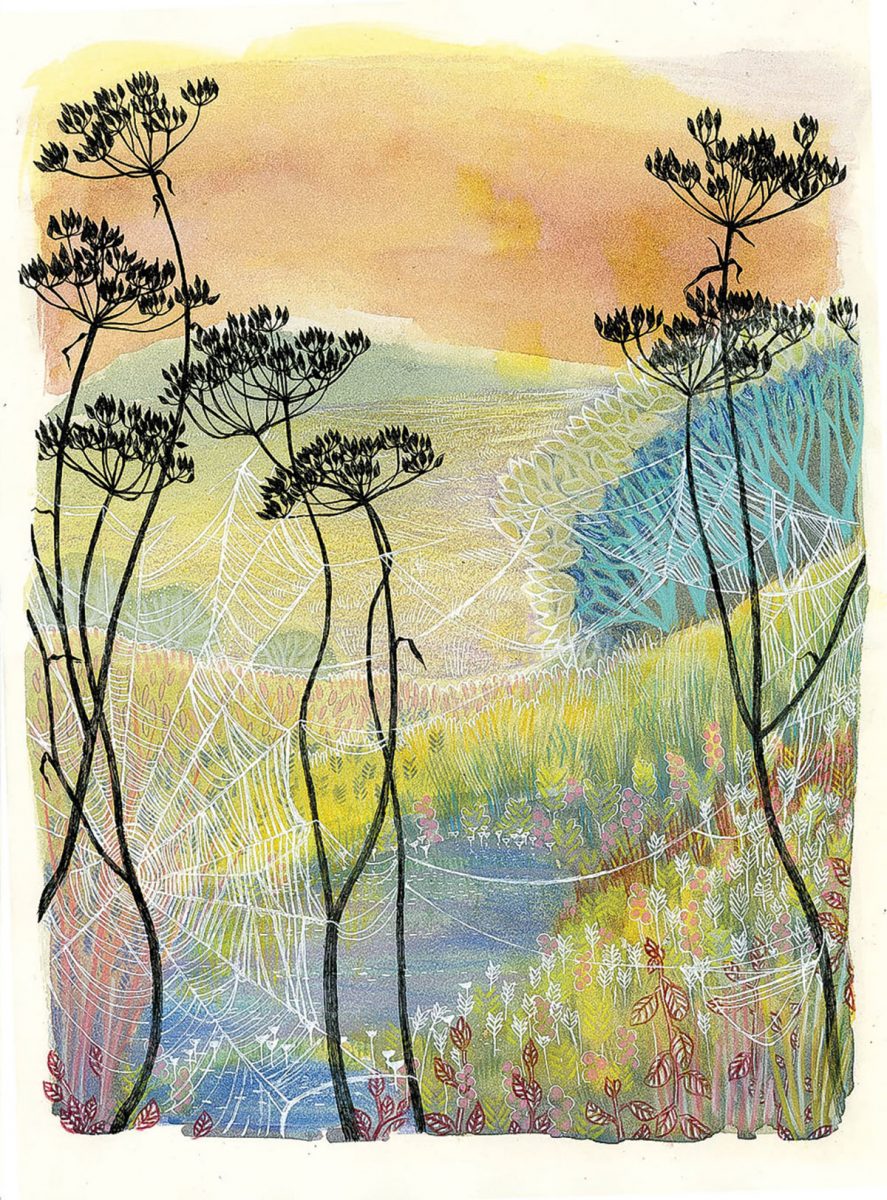

Maloney’s artwork is similarly grounded. Layers of charcoal, watercolors, and pen capture gossamer spider webs and wheeling goldfinches. Many prints are aquatic in spirit. “We Were on Our Bellies Looking In” depicts the rich biodiversity of Maine’s tidal pools — crimson starfish, periwinkle-tinged freshwater mussels, lime-green seaweed, humpback whales in deep blues and purples.

Maloney grew up Brunswick, Maine, where her mother was a florist and her father worked in the sailboat industry. Through their support, plus a public-school system with a robust arts program, she was actively encouraged to be an artist. “My parents always hung up my work, and still do,” says Maloney.

But beyond others’ validation, she lacked her own reason to create. She didn’t yet understand that art could be a tool for social change.

In 2012, after studying at the Moore College of Art & Design in Philadelphia, she and five friends bought a bus on eBay. They had hoped to drive to California to “break down assumptions” they had about themselves. Instead, the bus broke down in Burnsville, NC. Maloney was the only one of the five to stay.

At 24, she secured jobs drawing plants for botanists and herbalists, and a “slow trickle” of understanding became a loud, fast-flowing cascade. Maloney knew instinctually that she should create art to preserve the natural world. Art would be her medium of refusal — her terra-cotta bathtub.

But preservation requires dismantling, particularly of preconceived notions. “Think of scavengers. Without them, the bodies of animals — from humans to roadkill — wouldn’t break down,” says Maloney. “And yet people are grossed out by vultures with their bald heads and bloody beaks.”

She uses beauty and narrative to convey the interconnectedness of ecosystems. “Song to Life Underfoot” reveals the biodiversity of the rhizosphere: the region of soil that supports plant roots. A seed-packet commissioned by the Hudson Valley Seed Company, a business that works to preserve heirloom foodways, illustrates the circuitous relationships between watercress and indigenous people. “If we understand the plant’s history, we can understand how to better attend to the seed,” she says.

And while modern culture venerates the individual, particularly the individual’s ability to tame and monetize nature, Maloney’s art underscores the good in collectivism and in simply coexisting.

“I know how small I am,” she says. “But I also know how powerful the ripples are that I can create. We need to preserve a sense of place for future generations.”

Jacqueline Maloney, Celo. For more information, visit jacquelinemaloneyart.com. On Instagram: @jacquelinemaloneyart.