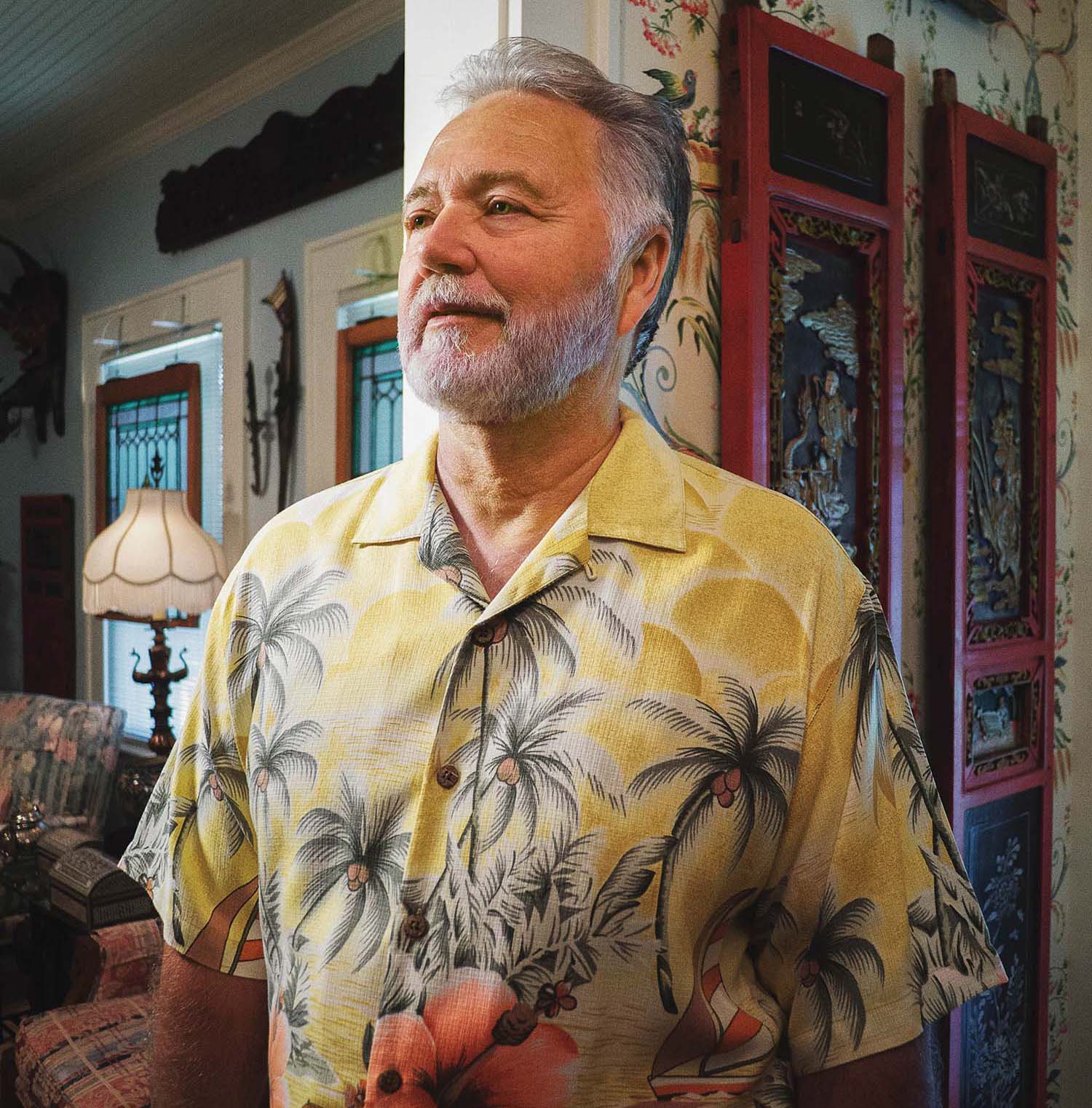

he’s collecting. Photo by Rimas Zailskas

During his 30 years living in his native Charleston, South Carolina, as a general contractor, David Ardis grew to appreciate fine craftsmanship. His specialty was redesigning old commercial properties from the Lowcountry’s maritime and plantation past. “I have always liked very intricately done items of very good workmanship no matter what the medium is,” says Ardis. Since retiring and moving to the Hendersonville area six years ago, he’s discovered some new objects of admiration in Islamic art, specifically the delicately worked and decorated metal trays in what is known as the Mamluk Revival style of the 19th and early 20th centuries.

He’s collected about 50 stunning metalware examples in the past five years, including one dated to the 17th century, the oldest in the collection. “It’s a private collection,” Ardis notes, which he has never exhibited publicly. “Most of the sources are out of England and certain areas in the Middle East.”

The Mamluks were to the Islamic world of 400 years ago what knights were to western Europe — a warrior class originating in the 10th century that, over the next 1,000 years, became a powerful political force from Egypt through present-day Iran and Iraq, from Syria to India. Mamluk sultans, beys, and pashas survived well into the late 19th century as protectors and administrators for the Ottoman Empire, and as their wealth and power grew, so did their luxurious lifestyle and interest in cultivating the arts. Among the everyday items that were transformed into art objects were the traditional metal plates, trays, and chargers used at mealtimes. These silver, brass and copper trays were worked with intricate filigrees, embossed with Arabic blessings for the patron who commissioned the work (“Fortune, joy, happiness, peace and long life to its owner,” reads one inscription), and were inlaid with botanical or animal designs. They were a part of the golden age of Islamic art, architecture, and literature in the 16th and 17th centuries, with Baghdad, Damascus, Cairo, and Mosul becoming important metalworking centers.

The pieces in Ardis’s collection were part of the response to European colonial ambitions in the Middle East during the 19th and early 20th centuries and the effort to recreate past glories in an “Arab style” as a unifying force against Western influences. “I like the Mamluk Revival period of the early 1800s, and what came to be known as Cairo Ware produced in Syria,” he explains. “The biggest bang for the buck you can get today is in those two categories.” While Ardis declines to attach a dollar value to any of the pieces in his collection, similar pieces can be found at online auction sites for anywhere from $50 apiece to more than $2,000.

Among the most appealing pieces in Ardis’s set is an oval copper tray depicting a polo game in painted enamel. It was made between 1880 and 1920 in Iran. The game is in full gallop in the rectangular courtyard of a palace framed with domed gates and minarets. In the foreground, a player is driving a goal home. Beyond the gates stretches a plain dotted with copper-green foliage, while craggy hills float on the horizon. The entire scene is bordered with floral designs against a deep blue background. While the easily worked copper of this particular example was popular with metal workers, brass and bronze were common, too, inlaid with silver designs or, less frequently, with precious gems. A hammered brass tray in Ardis’s collection, dated to about 1830 and probably produced in present-day Iraq, was etched by hand with delicate floral patterns surrounding a central lotus shape, a common design motif of the period.

Among the most appealing pieces in Ardis’s set is an oval copper tray depicting a polo game in painted enamel. It was made between 1880 and 1920 in Iran. The game is in full gallop in the rectangular courtyard of a palace framed with domed gates and minarets. In the foreground, a player is driving a goal home. Beyond the gates stretches a plain dotted with copper-green foliage, while craggy hills float on the horizon. The entire scene is bordered with floral designs against a deep blue background. While the easily worked copper of this particular example was popular with metal workers, brass and bronze were common, too, inlaid with silver designs or, less frequently, with precious gems. A hammered brass tray in Ardis’s collection, dated to about 1830 and probably produced in present-day Iraq, was etched by hand with delicate floral patterns surrounding a central lotus shape, a common design motif of the period.

The original inspirations for the flowering of Islamic art remain obscure, although it is known that the earliest surviving examples borrowed from the cultures of conquered Ottoman territories and perhaps even from Chinese forms that were transmitted along trade routes. “I’ve always believed that in general the Chinese are the most intricate wood carvers and the Middle East has the best metal carvers,” Ardis says, comparing the two major components of non-Western art history.

While he still keeps an eye out for attractive additions to his tray collection, Ardis’s most recent interest is antique wood picture frames decorated in gesso. “Over the last year or two I’ve been restoring the frames and repainting them in a colorful Art Nouveau style,” he reveals — bringing another area of craftsmanship to his appreciative eye.