When Carl Powell was working his way through art school at Georgia State University with a series of summer construction jobs, a friend who had been working at an Atlanta stained-glass studio decided to quit, and Powell stepped in. “It was a welcome opportunity to work with my hands on something more interesting, even though we were mostly making very traditional pieces,” he says. “Being rather isolated from other artists using stained glass, I didn’t know about a blooming glass-art scene in other parts of the country.”

This serendipity turned into a decades-long career combining contemporary art and innovative glassmaking techniques to produce a body of work incorporating large-scale commissioned projects with more personal, intimate items. Whatever the scale, Powell’s work is characterized by exquisite craftsmanship, original design, and a brilliant palette. “I always create my own designs, which are drawn in detail before the glass is involved,” he explains. Once the design is set, sections are cut to shape from large sheets of colored glass — a modern innovation over centuries-old methods using small glass sections that had to be fitted together like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle. In another contemporary improvement, the leading that binds adjacent sections now comes in long segments that can be custom cut, rather than the older, painstaking method of applying molten lead in shorter lengths.

The compositional integrity of Powell’s work likely stems from a lifelong attachment to the arts; he was given private classes, lessons in ceramics and painting, while barely in elementary school. During his college years, he studied painting, sculpture, and photography.

Photography in particular sparked a connection with glassmaking, as Powell developed his negatives in his own darkroom. “Working with the negatives very much influenced the direction of my glasswork,” he notes. “I began making leaded panels that … were like large black-and-white negatives.”

These panels, with their double-sided, ground-and-polished beveling, began to draw national attention, including a Fellowship in the early 1980s from the National Endowment for the Arts. At a conference in Toronto soon after, Powell met the influential glass artist Dale Chihuly and took up Chihuly’s offer to teach at his Pilchuck Glass School near Seattle, where Powell led workshops in stained-glass design and technique and met such important glassworkers as the late Czech artist Stanislav Libensky, credited with elevating glassmaking to the status of serious art.

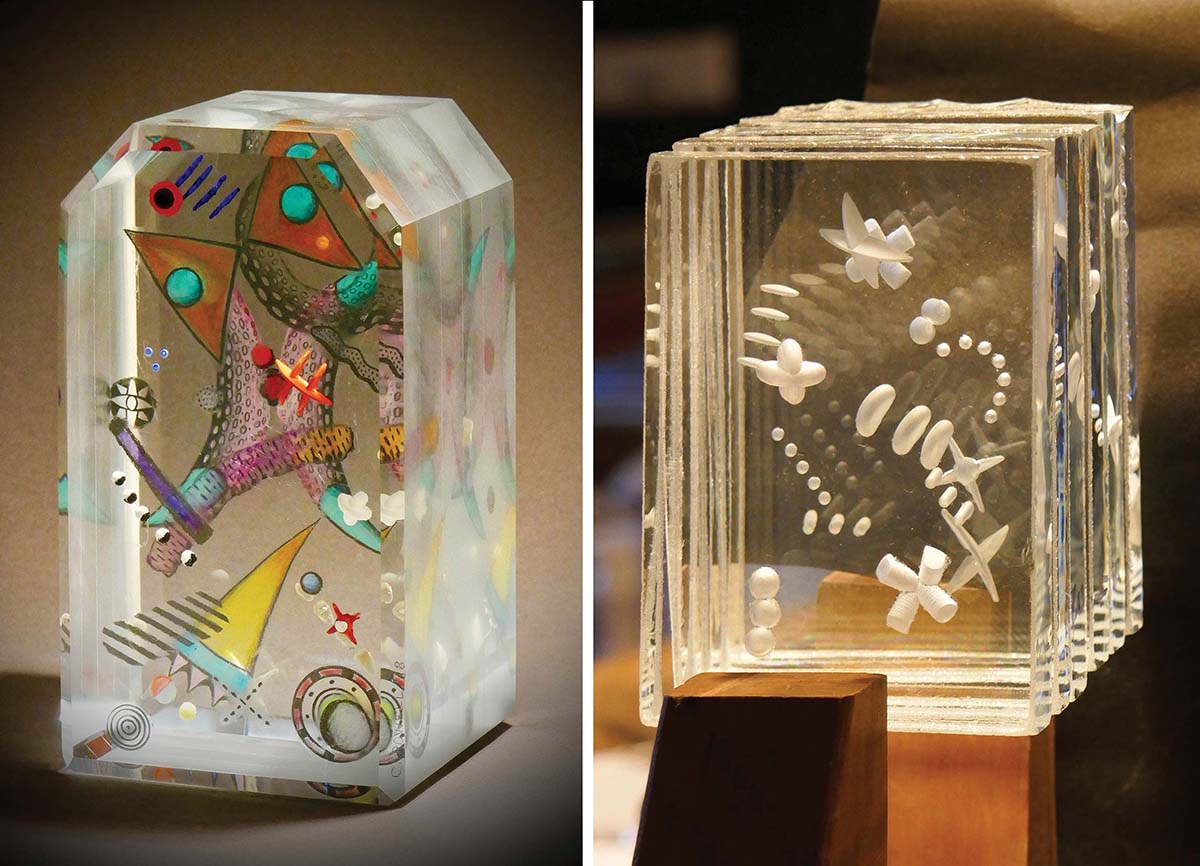

But in addition to sharing his own knowledge with students, Powell learned a new creative tool by laminating layers of glass to produce sculpture in which etched designs — sometimes mysterious, abstract colored shapes — seem to float in empty space. Powell describes them as 3D drawings. Or the glass may be combined with metal framing in a series of “Artifact” sculptures: “I imagine they could have been dug up from an ancient, mysterious civilization.”

Commissioned pieces were more difficult to accomplish during the past year-and-a-half of social isolation, but those already completed — outdoor sculptures or large-scale stained-glass installations in public buildings — brought a certain grace and relief from lockdown fever. Mission Children’s Hospital in Asheville features Powell’s clerestory installation of a planetary design, each colored orb traveling its own etched pathway. Visitors or passersby at the Van Dyke Performance Space at Greensboro Cultural Center can enjoy the iridescent blues and reds of the sculptor’s seven stained-glass windows, backlit and glowing in the evening light. “The designs for these larger commissioned works are usually influenced by the purpose of the building where they’re installed,” Powell says. “The Van Dyke [piece] comes from the feeling and flow of dancing.” (The space is dedicated to noted contemporary-dance virtuoso Jan Van Dyke.) His commissioned works are also sited in Atlanta, Barcelona, Mexico City, Oakland, San Francisco, and other major cities.

Powell continues to create on a more personal scale in his Grovewood Village studio, or at a cabin he owns near Penland School of Craft. When the pandemic began, he began working mainly on the laminated glass sculptures, because he could isolate and not have to meet with people for commissions. As the year still unfolds, more of his beguiling art will emerge into the light.

Carl Powell, studio visits by appointment in Mitchell County and in Asheville at Historic Grovewood Village (111 Grovewood Road, grovewood.com/artist/carl-powell/). For more information, see carlpowellglass.com.